The Kimono as a Symbol of Social Status in Japanese History: Kyoto’s Cultural Legacy

Discover how traditional Japanese kimonos represented social hierarchy and cultural identity throughout history, particularly in Japan’s ancient capital of Kyoto

- Introduction: Understanding the Kimono’s Cultural Significance

- The Historical Origins of Kimono Social Status

- Kimono Craftsmanship and Social Distinction

- The Edo Period: Merchant Class and Changing Dynamics

- Meiji Restoration and Modernization Impact

- Modern Kyoto: Kimono Culture Today

- The Art of Kimono Pattern Symbolism

- Economic Aspects of Kimono Social Status

- Regional Variations and Kyoto’s Distinctive Style

- Future Perspectives: Kimono Culture in the 21st Century

- Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Kimono Social Status

Introduction: Understanding the Kimono’s Cultural Significance

The kimono stands as one of Japan’s most recognizable cultural symbols, representing far more than simply traditional clothing. Throughout Japanese history, particularly in the imperial city of Kyoto, kimonos served as powerful indicators of social status, wealth, and cultural refinement. This ancient garment tells a fascinating story of class distinction, artistic expression, and cultural evolution that spans over a millennium.

In Kyoto, the former imperial capital of Japan, the kimono tradition reached its most sophisticated heights. The city’s rich history as the center of Japanese court culture, combined with its thriving textile industry, made it the epicenter of kimono fashion and social significance. Understanding the kimono’s role in Japanese society provides valuable insights into the country’s complex social hierarchy and cultural values.

The Historical Origins of Kimono Social Status

Ancient Court Culture in Kyoto

Jūnihitoe: The elaborate twelve-layer court dress of Heian period aristocratic women

The kimono’s association with social status began during the Heian period (794-1185), when Kyoto served as Japan’s imperial capital. During this era, the imperial court established elaborate dress codes that strictly regulated who could wear certain colors, patterns, and fabrics. These regulations, known as “sumptuary laws,” created a visual language of social hierarchy that could be read at a glance.

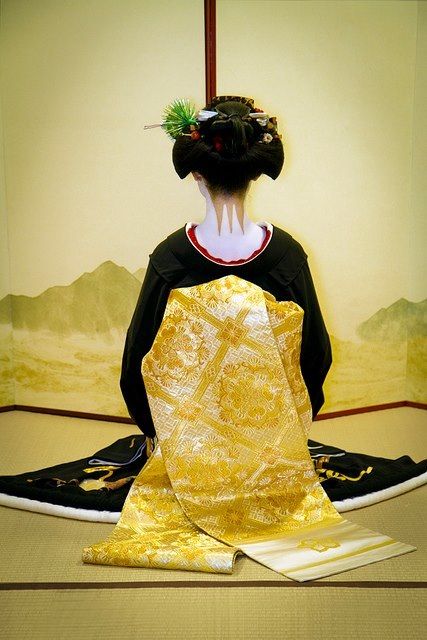

Aristocratic families in Kyoto competed to display their status through increasingly elaborate kimono designs. The number of layers worn, the quality of silk used, and the complexity of patterns all served as markers of nobility. Women of the highest social rank often wore twelve or more layers of silk kimono, each carefully coordinated to create stunning color combinations visible at the sleeves and hem.

Heian period court ladies displaying the sophisticated layering techniques that indicated social rank

The Color Hierarchy System

One of the most significant aspects of kimono social status was the color hierarchy system. Certain colors were restricted to specific social classes, with purple reserved exclusively for the imperial family. This tradition, deeply rooted in Kyoto’s court culture, created a sophisticated system of visual communication that persisted for centuries.

Purple kimono representing the exclusive imperial color hierarchy in traditional Japanese society

The production of these exclusive colors required expensive materials and complex dyeing processes, often involving rare minerals and plants. Kyoto’s artisans became masters of these techniques, developing secret methods passed down through generations of craftsmen. The city’s proximity to imperial power and its established textile workshops made it the natural center for producing the highest quality colored silks.

Kimono Craftsmanship and Social Distinction

Kyoto’s Textile Masters

Master weaver in Kyoto’s Nishijin district practicing traditional silk weaving techniques

Kyoto’s reputation as the center of Japanese textile arts stems from centuries of refinement and innovation. The city’s craftsmen developed sophisticated techniques for silk weaving, dyeing, and embroidery that became the standard for luxury kimono production. These artisans, organized into guilds, maintained strict quality standards and closely guarded their trade secrets.

The most prestigious kimono workshops in Kyoto employed dozens of specialized craftsmen, each responsible for specific aspects of production. Master weavers created intricate brocades, while dyers developed complex color palettes using traditional methods. Embroiderers added delicate details that could take months to complete on a single garment.

Regional Textile Techniques

Traditional textile workshop in Kyoto’s historic Nishijin district

Different districts within Kyoto became known for specific textile techniques that contributed to the kimono’s social significance. The Nishijin district, still famous today for its silk weaving, produced the most luxurious fabrics for the highest social classes. Meanwhile, other areas specialized in particular dyeing methods or decorative techniques.

These regional specializations created a complex ecosystem of kimono production that supported thousands of craftsmen and their families. The quality and origin of a kimono’s components could instantly communicate the wearer’s social position and economic resources to knowledgeable observers.

The Edo Period: Merchant Class and Changing Dynamics

Rise of the Merchant Class

During the Edo period (1603-1868), Japan’s social dynamics began shifting as the merchant class gained economic power. While legally positioned below samurai and farmers in the official social hierarchy, wealthy merchants in cities like Kyoto accumulated significant resources that they expressed through elaborate kimono.

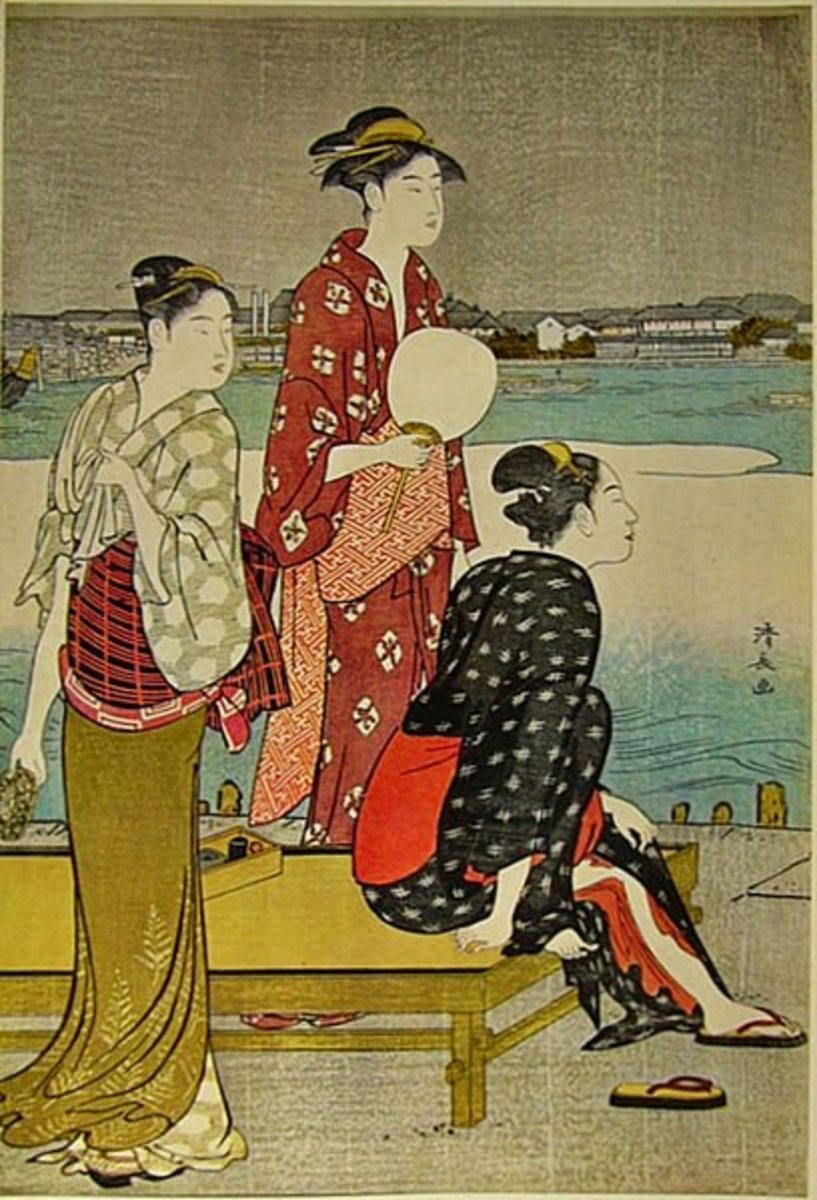

Edo period kimono showcasing the elaborate designs favored by the wealthy merchant class

This period saw the development of increasingly sophisticated kimono designs as merchants competed to display their wealth within the constraints of sumptuary laws. Clever artisans and wealthy patrons found ways to circumvent restrictions through subtle luxury—using expensive materials in hidden areas or employing complex weaving techniques that appeared simple but required extraordinary skill.

Urban Fashion Centers

Kyoto maintained its position as a fashion capital during this period, adapting to serve both traditional aristocracy and the emerging merchant elite. The city’s textile districts expanded and diversified, developing new products and techniques to meet changing demands while preserving traditional methods valued by conservative customers.

The competition between different social classes drove innovation in kimono design and production. Merchants sought to differentiate themselves through subtle displays of wealth, leading to the development of sophisticated aesthetic codes that required deep cultural knowledge to fully appreciate.

Meiji Restoration and Modernization Impact

Western Influence and Tradition

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought dramatic changes to Japanese society, including attitudes toward traditional dress. While the government promoted Western clothing for men in official contexts, kimono remained important markers of cultural identity and social status, particularly for women and in traditional settings.

Kyoto’s textile industry adapted to these changes by incorporating new materials and techniques while maintaining traditional aesthetics. The city’s craftsmen learned to work with imported fabrics and dyes while preserving the cultural significance of traditional designs and construction methods.

Preservation of Cultural Values

Despite modernization pressures, Kyoto’s role as the guardian of traditional Japanese culture helped preserve the kimono’s social significance. The city’s numerous temples, traditional ceremonies, and cultural events provided contexts where traditional dress codes continued to matter.

Educational institutions in Kyoto, including traditional arts schools and cultural academies, maintained formal instruction in kimono wearing and appreciation. This institutional support helped ensure that knowledge of kimono social codes survived the rapid social changes of the modern era.

Modern Kyoto: Kimono Culture Today

Contemporary Social Significance

In modern Japan, kimono continue to serve as symbols of cultural identity and social awareness, though their role has evolved significantly. In Kyoto, where traditional culture remains particularly strong, kimono wearing often indicates cultural sophistication and respect for Japanese heritage rather than strict social class.

Today’s kimono enthusiasts in Kyoto include people from diverse backgrounds who appreciate the garment’s artistic and cultural value. The city’s numerous kimono rental shops, traditional festivals, and cultural events provide opportunities for people to engage with this traditional form of dress regardless of their social or economic background.

Tourism and Cultural Experience

Modern visitors experiencing traditional kimono culture in Kyoto’s historic districts

Kyoto’s reputation as Japan’s cultural capital has made it a premier destination for visitors seeking authentic kimono experiences. The city’s historic districts provide perfect backdrops for kimono photography, and numerous businesses have emerged to serve this market.

For visitors looking to capture the beauty of Kyoto’s traditional culture, professional photography services like AllPhoto Kyoto offer expert assistance in creating stunning images that showcase both the elegance of traditional dress and the city’s magnificent historical settings.

Educational and Cultural Institutions

Kyoto’s universities, museums, and cultural centers continue to play important roles in preserving and transmitting knowledge about kimono culture. These institutions offer courses, exhibitions, and research programs that explore the historical significance of traditional dress and its contemporary relevance.

The city’s numerous textile museums and workshops provide hands-on educational opportunities for people interested in learning about kimono construction, design, and cultural significance. These programs help ensure that traditional knowledge continues to be passed to new generations.

The Art of Kimono Pattern Symbolism

Seasonal and Natural Motifs

Traditional kimono patterns and their symbolic meanings in Japanese culture

Traditional kimono patterns carry deep symbolic meanings that reflect the wearer’s cultural sophistication and social awareness. In Kyoto’s refined cultural environment, the ability to select appropriate seasonal patterns and understand their significance has long been considered a mark of good breeding and education.

Cherry blossoms, maple leaves, flowing water, and mountain scenes each carry specific associations and are considered appropriate for particular seasons or occasions. Masters of kimono culture can read these visual codes to understand not only the wearer’s aesthetic sense but also their cultural knowledge and social background.

Family Crests and Personal Identity

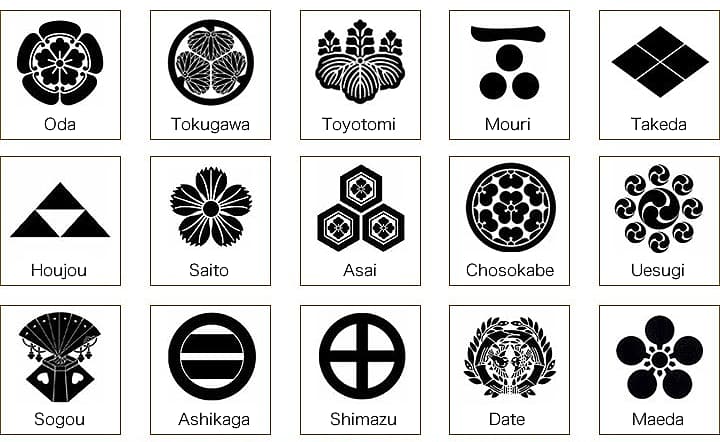

Traditional Japanese family crests (kamon) as displayed on formal kimono

Many formal kimono feature family crests (mon) that immediately identify the wearer’s lineage and social connections. In Kyoto’s traditional society, where family history and connections carry significant weight, these crests serve as important markers of identity and social position.

The placement, size, and style of family crests on kimono follow strict traditional rules that reflect the formality of the occasion and the wearer’s role in social hierarchy. Understanding these conventions requires deep cultural knowledge that has traditionally been passed down through families and cultural institutions.

Economic Aspects of Kimono Social Status

Investment in Cultural Capital

High-quality kimono represent significant financial investments that can serve as stores of value and symbols of economic success. In Kyoto’s traditional culture, families often maintain collections of kimono that are passed down through generations, representing both cultural heritage and economic assets.

The most prestigious kimono can cost tens of thousands of dollars, with rare antique pieces commanding even higher prices. This economic reality means that owning and wearing fine kimono continues to serve as a marker of economic success and cultural prioritization.

Artisan Economy and Cultural Preservation

Kyoto’s kimono industry supports a complex network of specialized craftsmen whose skills represent centuries of cultural development. The economic relationships between textile producers, designers, retailers, and customers help maintain traditional techniques and cultural knowledge.

This artisan economy faces challenges from modernization and changing consumer preferences, but Kyoto’s strong cultural identity and tourism industry provide important sources of support for traditional craftsmen and their families.

Regional Variations and Kyoto’s Distinctive Style

Kyoto vs Other Regional Styles

While kimono traditions exist throughout Japan, Kyoto’s particular history as the imperial capital created distinctive aesthetic preferences and cultural practices. The city’s kimono culture tends to emphasize subtle elegance, refined color palettes, and sophisticated pattern combinations that reflect centuries of court influence.

Compared to the more flamboyant merchant styles that developed in cities like Osaka, or the practical designs favored in rural areas, Kyoto kimono traditionally prioritized understated luxury and cultural sophistication over bold display or practical functionality.

Cultural Transmission and Regional Identity

Kyoto’s role as a cultural center means that the city’s kimono traditions often influence national standards and aesthetic preferences. The city’s numerous cultural institutions, traditional festivals, and educational programs help maintain and transmit these regional variations to broader audiences.

Visitors to Kyoto often seek to experience these distinctive local traditions, contributing to the preservation of regional kimono culture while also providing economic support for traditional craftsmen and cultural institutions.

Future Perspectives: Kimono Culture in the 21st Century

Digital Age and Traditional Culture

Modern technology has created new opportunities for preserving and sharing kimono culture while also presenting challenges to traditional practices. Social media platforms allow kimono enthusiasts to share their knowledge and experiences globally, while digital archiving projects help preserve historical examples and traditional techniques.

Kyoto’s cultural institutions have embraced these technologies to reach broader audiences while maintaining the depth and authenticity of traditional kimono education. Virtual museums, online workshops, and digital pattern libraries provide new ways to engage with traditional culture.

Sustainable Fashion and Traditional Crafts

Growing interest in sustainable fashion has brought renewed attention to traditional crafts like kimono making, which emphasize quality, durability, and timeless design over fast fashion trends. Kyoto’s traditional textile industry aligns well with these values, offering high-quality products that can last for generations.

This alignment with contemporary values provides new opportunities for Kyoto’s kimono culture to remain relevant while preserving traditional techniques and cultural significance.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Kimono Social Status

The kimono’s role as a symbol of social status in Japanese history reflects the complex interplay between culture, economics, and social organization that has shaped Japanese society for over a millennium. In Kyoto, where traditional culture maintains particularly strong roots, the kimono continues to serve as a bridge between historical tradition and contemporary cultural identity.

Understanding the kimono’s social significance provides valuable insights into Japanese cultural values and the ways that material culture can encode and transmit social information across generations. As Japan continues to evolve in the modern era, Kyoto’s preservation of traditional kimono culture ensures that this important aspect of Japanese heritage remains accessible to future generations.

Whether worn for special occasions, cultural ceremonies, or simply as expressions of personal aesthetic preference, kimono continue to carry the weight of their historical significance while adapting to contemporary contexts. In Kyoto, this living tradition demonstrates how cultural practices can maintain their essential character while evolving to meet the needs of changing times.

For visitors seeking to experience this rich cultural tradition firsthand, Kyoto offers unparalleled opportunities to engage with authentic kimono culture in settings that have preserved their historical significance for centuries. The city’s commitment to maintaining traditional crafts and cultural practices ensures that the kimono’s role as a symbol of cultural sophistication and aesthetic refinement will continue to enrich Japanese society for generations to come.

コメント